Threads and Processes

Process

- When a computer runs an application, that instance of program executing is referred to as a process.

- A process consists of program’s code, data and its information about its state. Each process is independent and has its own address space and memory.

- A computer can have hundreds of active processes and an operating system’s job is to manage all of them.

Threads

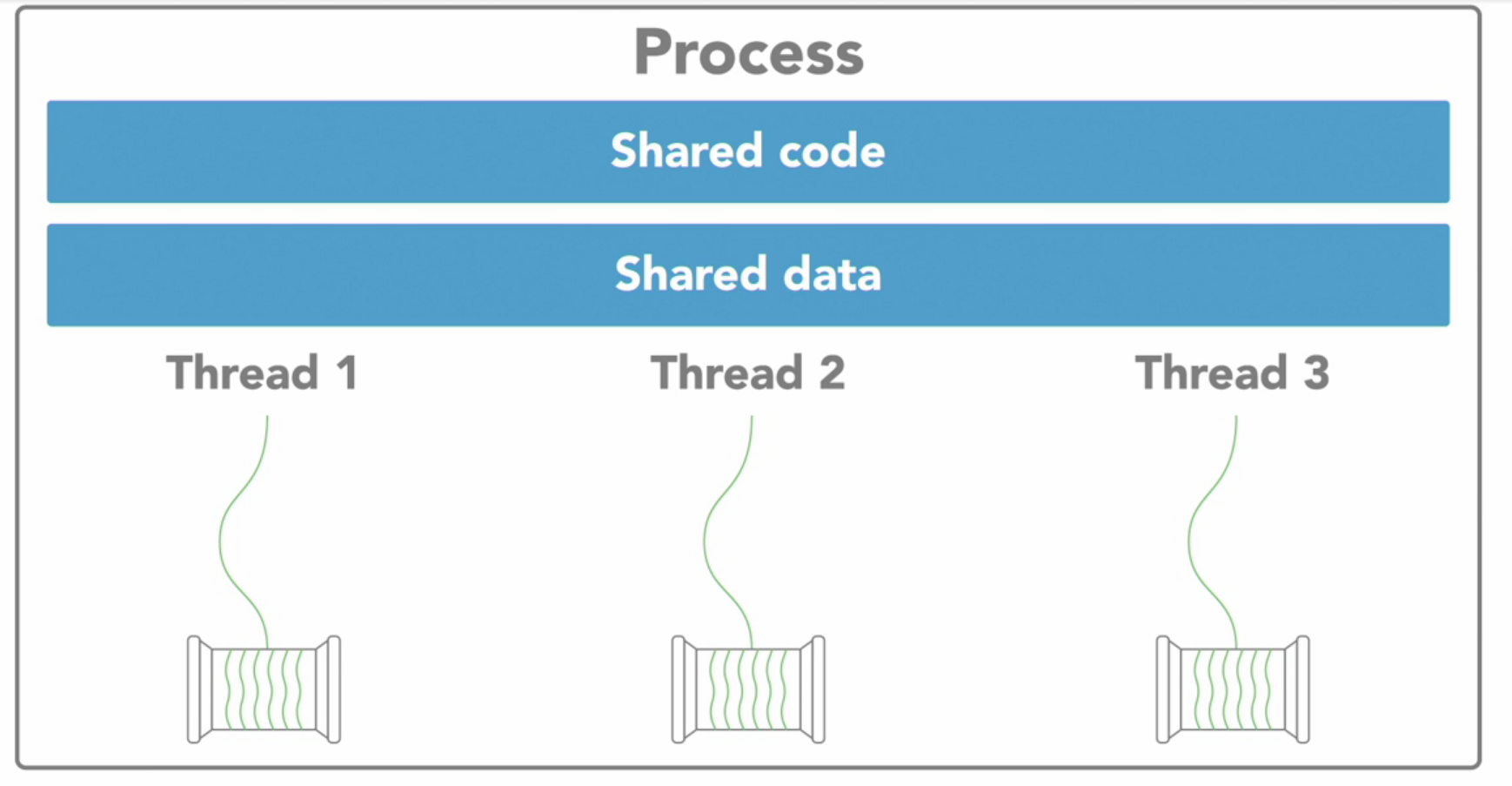

Now within each process there are one or more sub elements called threads. These are kind of like tiny processes.

Each of those threads is an independent path of execution through the program, a different sequence of instructions. And it can only exist as a part of the process.

Threads are basic units that operating system manages, and it allocates time on the processor to actually execute them.

Threads work independently doing their own tasks which contribute to the overall execution of the process.

According to requirement new threads can be created and as soon as they finish their task they can exit the process.

Threads that belong to the same process share the process’s address space which gives them access to the same resources and memory including the program’s executable code and data. But there has to be coordination between threads while accessing resources otherwise problems like race condition might arise which we’ll study later.

Sharing resources between processes is not as easy as sharing between threads in the same process, because every process exists in its own address space.

Inter-process communication

There are ways to communicate between processes but it requires a bit more work than communicating between threads. We can do this by using

- Sockets and pipes

- Allocating special inter-process shared memory space

- Remote procedure calls

Now it’s possible to write parallel programs that use multiple processes working towards a common goal or multiple threads. So which is better? Well it depends because the implementation of threads and processes differ between operating systems and programming languages.

If your application is going to be distributed among multiple computers, then its better to use multiple processes. But as a rule of thumb, if you can structure a program to take advantage of multiple threads than stick with threads because

- Threads are light-weight, it means they require less overhead to create and terminate.

- Operating system can switch faster between threads than processes.

Concurrency vs Parallelism

Just because a program has multiple threads or processes doesn’t mean they’ll execute in parallel.

- Concurrency refers to the ability of program to be broken into different parts which can be executed out of order, or partially out of order without affecting the end result.

Concurrency, the idea of executing multiple tasks and constantly switching between them creating an illusion of parallelism.

Actual parallelism would be two things executing simultaneously at one point of time and for that we need more than one CPU.

In a CPU which has single core, you can only have concurrency you cannot have parallelism.

Concurrency enables a program to execute in parallel, given the necessary hardware, but a concurrent program is not inherently parallel. And programs may not always benefit from parallel execution.

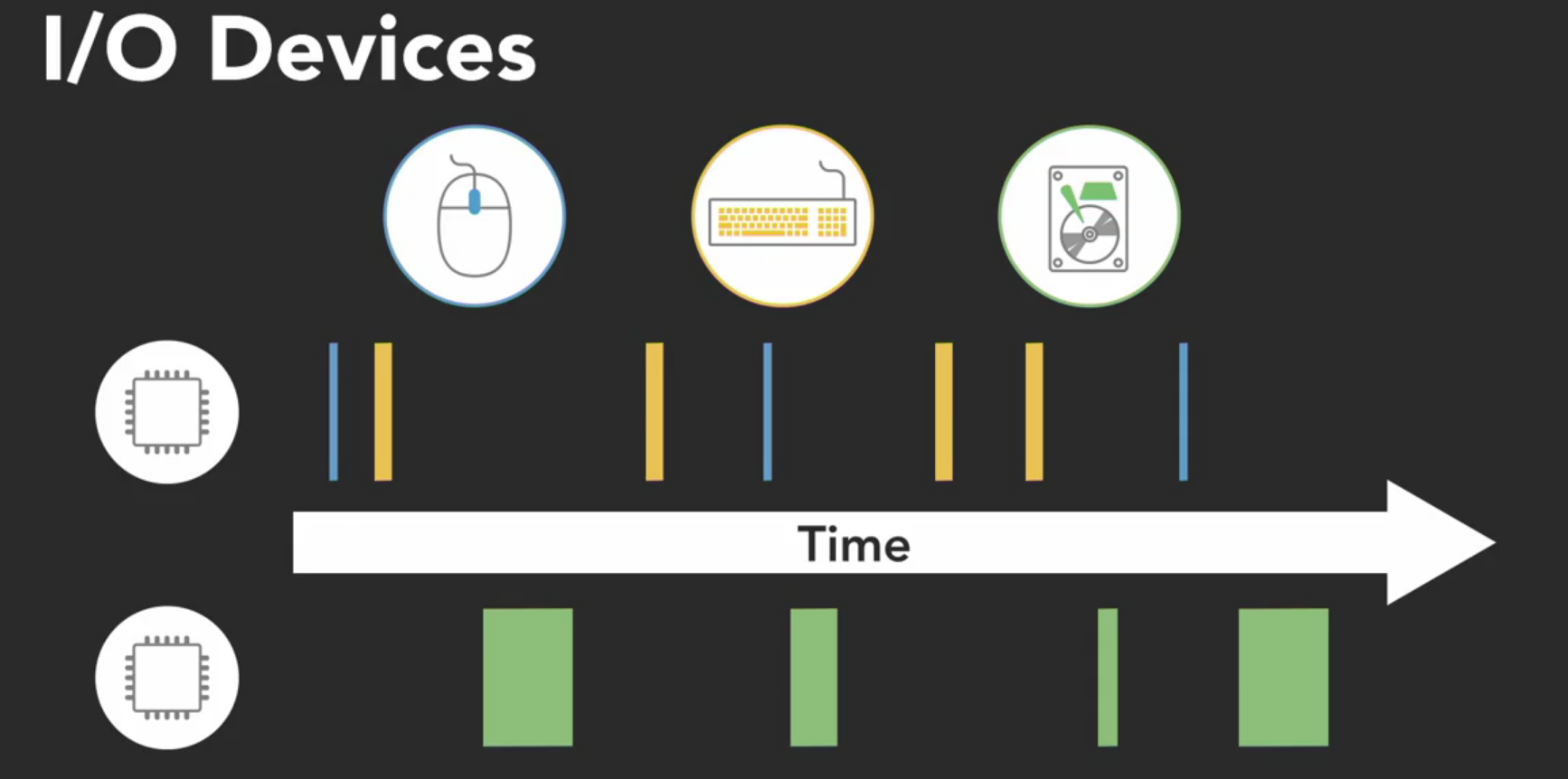

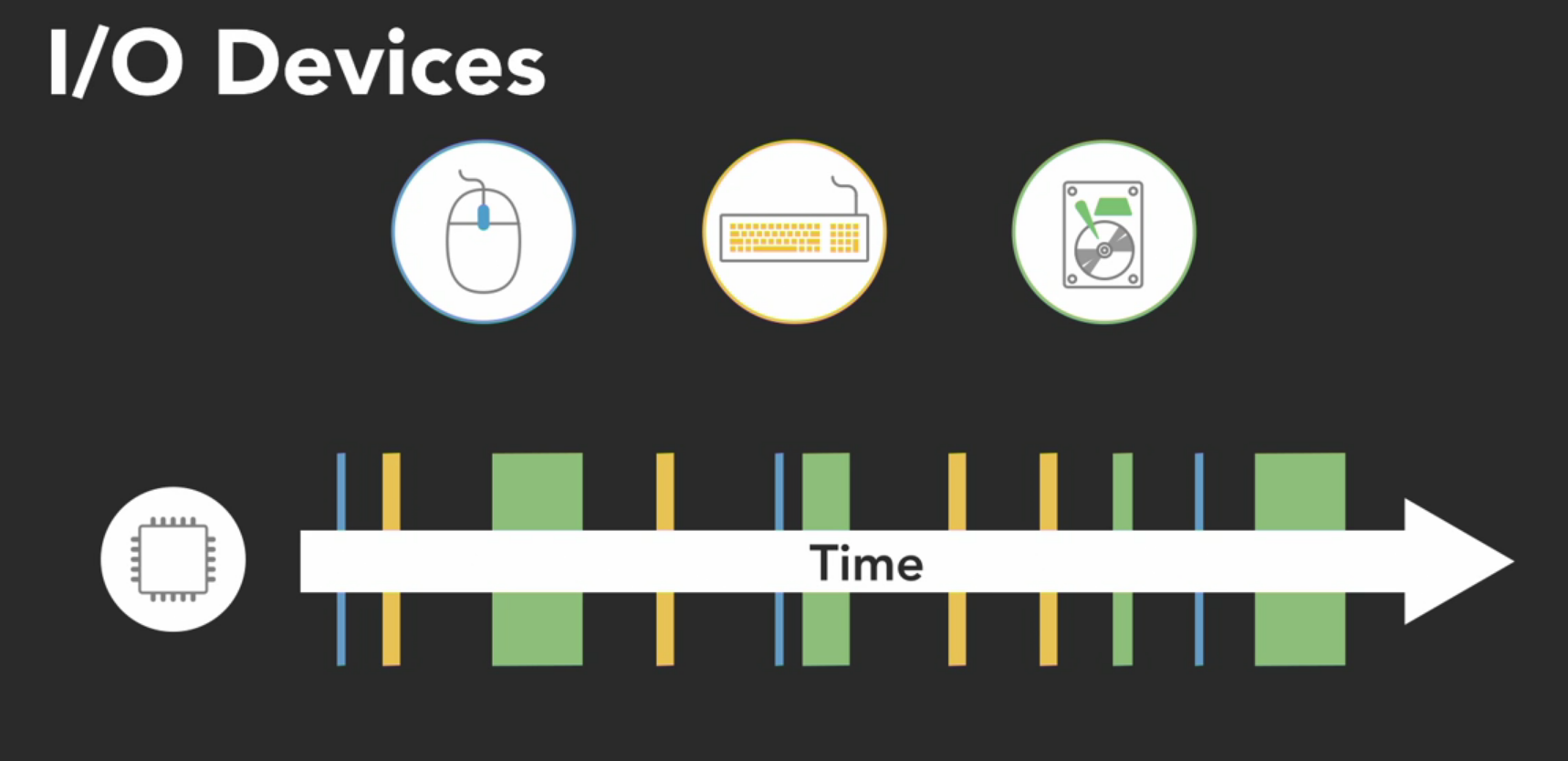

For example, the software drivers that handle I/O devices like a keyboard, mouse or a hard drive, need to execute concurrently. They’re managed by the operating system as independent things need to get executed as needed. In a multi-core system, the execution of those drivers might get split amongst the available processors.

However since the I/O operations occurs rather infrequently, relative at which computer operates, we don’t really gain anything from parallel execution. Those sparse independent tasks could run just fine on a single processor, and we wouldn’t feel the difference.

Concurrent programming is useful for I/O dependent tasks, like graphical user interfaces. When the user clicks a button to execute an operation that might take a while, to avoid locking up the user interface until its completed, we can run the operation in a separate concurrent thread. This leaves the thread that’s running the UI free to accept new inputs. That sort of I/O dependent task is good use case for concurrency.

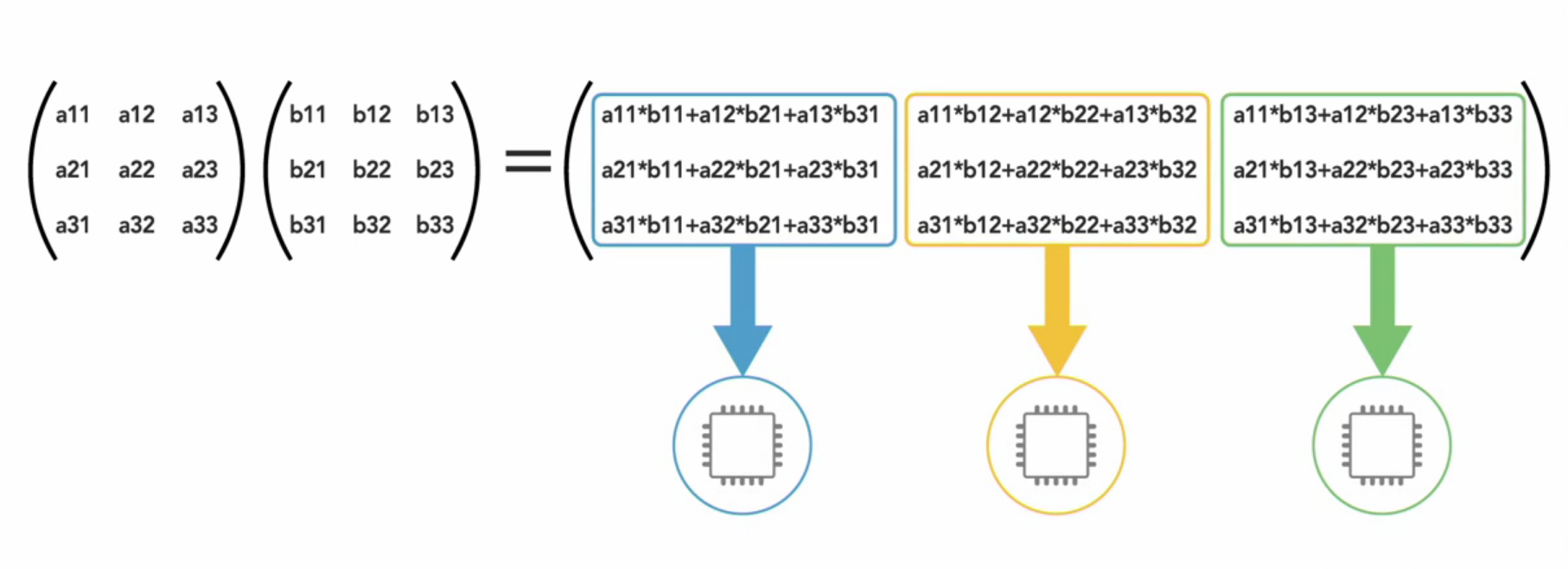

Parallel processing really becomes useful for computationally intensive tasks, such as calculating the result of multiplying two matrices together.

When large math operations can be divided into independent subparts, executing those parts on separate processors can really speed things up.

In a multithreaded process on a single processor, the processor can switch execution resources between threads, resulting in concurrent execution. Concurrency indicates that more than one thread is making progress, but the threads are not actually running simultaneously. The switching between threads happens quickly enough that the threads might appear to run simultaneously.

In the same multithreaded process in a shared-memory multiprocessor environment, each thread in the process can run concurrently on a separate processor, resulting in parallel execution, which is true simultaneous execution. When the number of threads in a process is less than or equal to the number of processors available, the operating system’s thread support system ensures that each thread runs on a different processor. For example, in a matrix multiplication that is programmed with four threads, and runs on a system that has two dual-core processors, each software thread can run simultaneously on the four processor cores to compute a row of the result at the same time.

For more on this, read from here

Global Interpreter Lock(GIL)

The python interpreter will not allow concurrent threads to execute simultaneously and parallel, due to a mechanism called Global Interpreter Lock. It’s something that unique to python. That means if your program is written to have 10 concurrent threads, only one of them can execute at a time while the other nine wait their turn.

For I/O bound operations, GIL is not a bottleneck and we can easily write are programs which are I/O heavy.

For CPU bound applications, we can use multiprocessing package of python or we can write external libraries in C++ which can be called from python.

Multiple Threads

A sample threads program

import os

import threading

# a simple function that wastes CPU cycles

def cpu_waster():

while True:

pass

# displays information about process

print(f"Process ID : {os.getpid()}")

print(f"Thread count : {threading.active_count()}")

for thread in threading.enumerate():

print(thread)

print("\n Starting 12 CPU wasters")

for _ in range(12):

threading.Thread(target=cpu_waster).start()

# displays information about process

print(f"Process ID : {os.getpid()}")

print(f"Thread count : {threading.active_count()}")

for thread in threading.enumerate():

print(thread)

OUTPUT :

Process ID : 16664

Thread count : 1

<_MainThread(MainThread, started 140709757151040)>

Starting 12 CPU wasters

Process ID : 16664

Thread count : 13

<_MainThread(MainThread, started 140709757151040)>

<Thread(Thread-1, started 140709724800768)>

<Thread(Thread-2, started 140709716408064)>

<Thread(Thread-3, started 140709638174464)>

<Thread(Thread-4, started 140709629781760)>

<Thread(Thread-5, started 140709621389056)>

<Thread(Thread-6, started 140709612996352)>

<Thread(Thread-7, started 140709604603648)>

<Thread(Thread-8, started 140709596210944)>

<Thread(Thread-9, started 140709587818240)>

<Thread(Thread-10, started 140709034194688)>

<Thread(Thread-11, started 140709025801984)>

<Thread(Thread-12, started 140709017409280)>

Multiple Processes

Here’s an example

import os

import threading

import multiprocessing as mp

# a simple function that wastes CPU cycles

def cpu_waster():

while True:

pass

# displays information about process

print(f"Process ID : {os.getpid()}")

print(f"Thread count : {threading.active_count()}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

for thread in threading.enumerate():

print(thread)

print("\n Starting 12 CPU wasters")

for _ in range(12):

mp.Process(target=cpu_waster).start()

# displays information about process

print(f"Process ID : {os.getpid()}")

print(f"Thread count : {threading.active_count()}")

for thread in threading.enumerate():

print(thread)

OUTPUT :

Process ID : 17046

Thread count : 1

<_MainThread(MainThread, started 140530896164672)>

Starting 12 CPU wasters

Process ID : 17046

Thread count : 1

<_MainThread(MainThread, started 140530896164672)>

Execution Scheduling

The OS includes a scheduler that controls when different threads and processes get their turn to execute on CPU.

The Scheduler makes it possible for multiple programs to run on single processor.

When the process is created and ready to be executed, it gets loaded into memory and placed in the ready queue.

The scheduler cycles through the ready processes so they get a chance to execute on the processor. If there are multiple processors, then OS will schedule processes to run on each of them to make the most use of additional resources.

A process will run until it finishes(well not exactly :smile: wait until you read scheduling algorithms), and then a scheduler will assign another process to execute on that process.

Or a process might get blocked and have to wait for an I/O event, in which case it’ll go into separate I/O waiting queue so another processes can run.

Or a processor might determine that a process has spent its fair share of time on the processor, and swap it out for the another process from the ready queue. When that occurs, it’s called Context Switch.

The operating system has to save the state or context of the process that was running so it can be resumed later, and it has to load the context of new process that’s about to run.

Context switches are not instantaneous. It takes time to save and restore the registers and memory state, so the scheduler needs a strategy for how frequently it switches between the processes. Here are some scheduling algorithms

- First come, first serve

- Shortest job next

- Priority

- Shortest time remaining

- Round-robin

- Multiple-level queues

Some of these algorithms are preemptive which means they’ll pause or preempt a running, low-priority task when a higher priority task enters. In non preemptive algorithms, once a process enters the state, it’ll be allowed to run for its allotted time.

Which algorithms scheduler implements depends upon its goals as. Following can be the goals of schedulers according to which the algorithm they implement might change.

Some schedulers might try to maximize throughput , or amount of work they complete in given time, whereas others might aim to minimize latency to increase system’s responsiveness.

Different operating systems have different purposes, and a desktop OS like windows will have a different set of goals and use a different type of scheduler than a real time OS for embedded systems.

Important thing to remember is

Avoid running programs expecting that multiple threads or processes will execute in a certain order, or for an equal amount of time, because the OS may choose to schedule them differently from run to run.

Thread Execution

Here’s an example

import threading

import time

chopping = True

def vegetable_chopper():

name = threading.current_thread().name

vegetable_count = 0

while chopping:

print(f"{name} chopped a vegetable!")

vegetable_count += 1

print(f"{name} chopped {vegetable_count} vegetables!!")

if __name__ == '__main__':

threading.Thread(target=vegetable_chopper, name="Sheldon").start()

threading.Thread(target=vegetable_chopper, name="Leonard").start()

time.sleep(1)

chopping = False

For the above example the output will always be different every time you run it